Leg Ulcers: Associated with Sickle Eye Disease

Received: 04-Jul-2022 / Manuscript No. JCEC-22-68417 / Editor assigned: 08-Jul-2022 / PreQC No. JCEC-22-68417 (PQ) / Reviewed: 22-Jul-2022 / QC No. JCEC-22-68417 / Revised: 29-Jul-2022 / Manuscript No. JCEC-22-68417 (R) / Published Date: 05-Aug-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000414.

Abstract

Leg ulcers are a common sign in Sickle Cell Disease. But to what extent are they indicative of Sickle cell eye disease in these patients? This short communication, examines to determine to what extent leg ulcers predict the presence of sickle eye disease.

This was a clinic based, comparative non-interventional study, conducted at both the Hematology Clinic and Eye clinic in Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). One hundred consecutive cases of Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) patients (HbSS and HbSC) attending the Haematology Clinic were compared with 100 age and sex matched non- SCD HbAA controls. The presence of leg ulcers was sought in both groups, and all had assessment for ocular anterior and posterior signs of SCD. Cases and controls were comparable in age and sex. Amongst 100 Cases, 85 were HbSS and 15 HbSC. Leg ulcers were present in 18 patients (cases). Eighty-two cases had either anterior or posterior SCD related ocular manifestations. Patients with leg ulcer were found to be at higher risk of developing Conjunctival Sickle Sign, Retinal Venous Tortuosity and Proliferative Sickle Retinopathy with an increased likelihood of 22.9, 7.1 and 5.9 times respectively. We believe this is the first study to quantify this association.

This study suggests that sickle cell eye disease is more likely to develop in sickle cell disease patients with leg ulcers. Internists managing SCD patients are advised to refer patients with leg ulcers for early ocular assessment in order to prevent complications.

Keywords: Leg ulcers; Sickle cell eye disease; Proliferative retinopathy

Abbreviations

BIO: Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscopy; CSS: Conjunctival Sickle Sign; CI: Confidence Interval; GEC: Guinness Eye Centre; HbAA: Hemoglobin AA; HbAS: Hemoglobin AS; HbAC: Hemoglobin AC; HbSS: Hemoglobin SS; HbSC: Hemoglobin SC; LUTH: Lagos University Teaching Hospital; OR: Odd’s Ratio; PSR: Proliferative Sickle Retinopathy; RVT: Retinal Vascular Tortuosity

Introduction

Sickle cell disease refers to a group of genetic disorders characterized by the presence of sickled red blood cells, anemia, as well as acute and chronic tissue injury secondary to blockage of blood flow by abnormally shaped red blood cells [1].

The rigid sickled erythrocytes cause disruption of blood flow leading to vascular occlusions, hemorrhage, infarctions and ischaemic necrosis of tissues and organs in the body including the eyes. The disease is found almost exclusively in blacks with no gender predilection [2].

The ocular manifestations of sickle cell disease result from vascular occlusion, which may occur in the conjunctiva, iris, vitreous, retina,and choroid3. The occurrence of these ophthalmic manifestations has been well documented in literature [3-5]. However less documented and elucidated are attended risk factors that could predispose one developing sickle cell eye disease in adult patients living with sickle cell disease. As treatment modalities improve, individuals with sickle cell disease live longer thus increasing the incidence of sickle cell related eye disease [6,7]. With Nigeria having the largest population of people with sickle cell disorder in the world more of the population is at risk of the blinding complications and other ocular problems [8]. There is therefore a need for more awareness on the ocular morbidities associated with sickle cell disease, and the elucidation of factors that could point to potential blinding disease.

Leg ulceration occurs in SCD, especially in the monozygotic HBSS disease [9-11]. The mechanism may include mechanical obstruction of blood flow by log jammed sickled cells, and decreased nitric acid bioavailability [12]. Leg ulcers are most commonly found in areas of the body with low subcutaneous fat such as the medial and lateral malleolus [13]. Akinyanju, et al. reported a leg ulceration prevalence of 1.4% in SCD patients in Lagos and indicated that it tended to be commoner in males than females [10].

We recently carried out a study in Lagos in which ocular and physical changes in sickle cell disease patients were simultaneously observed. In this short communication, we wish to report on the relationship between leg ulcers and ocular disease, and determine to what extent if any leg ulcers are a risk factor for ocular disease.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) Ethics and Research Committee (ADM/DCST/ HREC/372), adhering to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki [14].

The study was conducted at both the Haematology Clinic and Guinness Eye Centre (GEC) of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) Idi-Araba Lagos, which is the largest referral center in the region, between February 29 and April 11 2012. The cases were made up of sickle cell disease patients (genotypes HbSS, HbSC) aged 16 years while the controls were age and sex matched patients with genotype HbAA drawn from consenting accompanying relatives.

Patients with systemic co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, HIV/AIDS, lymphomas, and bleeding disorders like hemophilia were excluded from the study.

All the study subjects were counseled individually on the nature of the study and informed written consent obtained before proceeding with the study. Detailed Systemic and ocular examination were conducted by a consultant hematologist and then ophthalmologist.

All participants were examined with a slit lamp biomicroscope at 12x magnification for anterior segment manifestations. Dilated fundoscopy was done followed by binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy to examine the fundus of all participants. Grading of sickle cell retinopathy was according to Goldberg’s classification [15].

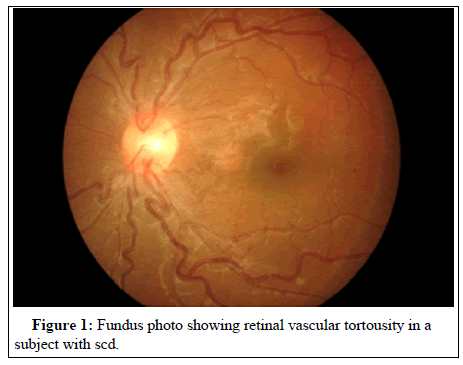

Selected cases had pictures taken of their anterior segment manifestations and fundal photography. Pictures were taken of some cases of ocular findings of Figures 1 and 2 and leg ulcers in Figures 3 and 4.

Findings were collated and analyzed with SPSS 20. Means were compared using the student t test. Chi square and simple logistic regression was done to measure the strength of association.

Results

A total of 200 subjects participated in the study, 100 cases with sickle cell disease (85 HbSS and 15 HbSC) and 100 HbAA (controls). The two groups were statistically comparable in terms of age and sex Age range was 16-58 years mean age 27.55 ± 8.53 (cases) 26.85 ± 8.77 (controls). Females slightly outnumbered males (Male: female 1:1.4) Distribution of visual acuity was similar in both groups (Table 1).

| Visual acuity | Cases N (%) | Controls N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 6/5-6/12 | 90 (90) | 92 (92) |

| <6/12-6/18 | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| <6/18-3/60 | 5 (5) | 6 (6) |

| ≤ 3/60 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

Table 1: Visual acuity in 200 cases and controls.

5 and 6 patients respectively in the case and control group had VA less than 6/18, while only 2 of the cases had VA less than 3/60 (Blind). Eighty-two of 100 cases had either anterior or posterior ocular manifestations compatible with sickle cell disease which was found in none of the controls. Conjunctival Sickle Sign (CSS) was present in 63 cases while controls had none.

Typical Non-proliferative posterior segment lesions were found in the cases and included Retinal Vascular Tortuosity RVT (17), Salmon patch hemorrhage (1), Black sunburst (9) and Angioid Streak (1). Only 1 case of what appeared to be RVT was found in the control group (Table 2).

| Variable | Cases N (%) | Controls N (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal vascular tortuosity | 17 (17) | 1 (1) | 18 (9) |

| Salmon patch hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Black sunburst | 9 (9) | 0 | 9 (4.5) |

| Angioid streak | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

Table 2: Non-Proliferative Retinopathy in cases and controls.

Proliferative Sickle Retinopathy was present in 9 of the 100 cases, but none of the controls. However, it was more prevalent in the SC disease arm than the SS arm (25% versus 7.6%) OR 3.29 (95% CI 0.73-14.95), P=0.06 (Table 3).

| Any Retinopathy | SS | SC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 79 | 12 | 91 |

| Present | 6 (7.6%) | 3(25%) | 9 (9%) |

| Total | 85 | 15 | 100 |

Table 3: Proliferative sickle cell retinopathy (PSR) by genotype SC and SS.

This is just short of statistical significance, probably because of low numbers, but it suggests that patients with SC diseases are more than thrice as likely to develop PSR as SS patients. None of the signs of Posterior Sickle retinopathy were found in the control Arm (AA). Leg ulcers were found in 18 individuals out of the total of 200 in the study (Figure 1). As indicated in Table 4, leg ulcers were proportionately commoner in patients with Conjunctival Sickle Sign, Retinal Vascular Tortuosity, and sickle Cell Retinopathy in general. The Odds ratios were 22.98, 7.08 and 5.87 respectively, all of which were statistically significant (Table 4).

| Leg ulcer | Present (%) | Absent | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSS present | 16(25.4) | 47 | 22.94 | 5.09-103.71 | 0 |

| CSS absent | 2 (1.5) | 135 | |||

| RVT present | 6(33.3) | 12 | 7.08 | 2.26-22.18 | 0.02 |

| RVT absent | 12(6.6) | 170 | |||

| SCret Present | 3(33.3) | 6 | 5.87 | 1.33-25.84 | 0.037 |

| SCret Absent | 15(7.9) | 176 |

Table 4: Distribution of leg ulcers and ocular pathologies.

Discussion

The link between leg ulceration and sickle cell eye disease has been drawn in this study; particularly to the effect that retinopathy is six to seven times commoner in patients with leg ulceration. This, as far as we can tell, is the first time this link will be made, even if it is logically to be expected. This is important because physicians who would generally take care of patients with leg ulcers are not often equipped or inclined to examine the back of the eye, where potentially blinding complications can occur. Early referral to ophthalmologists can lead to sight-saving intervention with the use of scatter lasers or anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) therapy, systemic therapy with hydroxycarbamide or hydroxyurea, exchange transfusion, and hyperbaric oxygenation. Surgical management such as vitrectomy and retinal detachment surgery may be indicated for recalcitrant vitreous hemorrhage. However, exoplants should be used with caution to obviate the risk of retinal ischemia [16].

By the same token, ophthalmologists who tend to focus on eye examination alone are encouraged to examine patients more holistically, particularly for leg ulcers, so that appropriate intervention may be instituted upon referral.

There are probably overlapping pathways in the development of Sickle retinopathy and leg ulcers. Trent, et al. has hypothesized on various mechanisms for the development of skin ulcers in sickle cell disease [17]. These include microvascular occlusion, secondary inflammation through release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, platelet aggregation, pro-coagulant cascade, ischemic injury and end organ damage. De Oliviero et al. also hypothesized that oxidative stress plays a role in the pathogenesis of ulcers, especially in patients with glutathione S-transferase polymorphism (GSTM1 and GSTT1 null phenotypes) [18]. Other mechanisms include autonomic dysfunction of microvascular circulation [19] and bacterial colonization involving the ulcer skin microbiome [20]. As yet poorly understood genetic factors also likely play a role, given the wide geographical variability in the incidence of the disease [21].

By the same token, the pathogenesis of Sickle cell disease ocular disorders has been assessed by Emmerson, et al. [22,23]. The normal malleability of red blood cells RBCs allow them to pass through smaller blood vessels especially capillaries. In SCD, the RBCs take up a rigid, sickle shape in hypoxic conditions due to conversion of soluble hemoglobin to crystalline hemoglobin, an irreversible change. In addition, there is an increase in the adhesive properties of the capillary endothelium which further decreases vascular flow and causes occlusion of the vessels. The log-jamming of end vessels in the eye cause the characteristic damage seen in SCD. Where vasoproliferative changes supervene, the changes called Proliferative Sickle Retinopathy are seen, with hypoxia and secondary hemorrhage.

The management of leg ulcers is unfortunately, not straightforward. Management generally includes the optimal hematological care of the condition, pain management, and compression therapy, review of walking and footwear, and regular assessment of tissue viability [24]. Nwagu, et al. also advocated the use of Honey combined with transfusion with HbAA blood in the management of the condition [25].

The earlier these treatment modalities are instituted, the better the prognosis for skin ulcer care. One important difference of course, is that while skin ulcers are commoner in homozygous HbSS disease retinopathy is commoner in HbSC disease [26-28].

Conclusion

In summary, because of the increased risk of visual complications in patients with sickle leg ulcers, it is important for attending physicians to refer patients with leg ulcers early for ophthalmological assessment. Equally, ophthalmologists should be on the lookout for leg ulcers when they are assessing SCD patients for eye disease, so that early intervention can be brought about. In this paper, we have drawn the link between Sickle Cell leg ulcers and Sickle cell retinopathy. This is the first time such a link will be drawn as far as we can tell. This link is very important because patients who have leg ulcers will often be treated at the Sickle Cell clinic often without reference to the ophthalmology unit. Hence, we hope this paper will alert hematologists, especially those practicing in areas endemic for sickle cell disease such as West Africa, The West Indies and the United States, to promptly refer such patients for ophthalmic assessment, so that intervention can begin.

Recommendations

• It is recommended that sickle cell disease patients especially HbSC should have full medical examination including routine eye examination to optimize their eye care-for early diagnosis and prompt treatment of blinding complications.

• Multidisciplinary approach to the management of sickle cell disease through a regular communication between the ophthalmologists and other health care givers, especially Haematologists, should be encouraged.

• Haematologists and all doctors attending to sickle cell disease patients with leg ulcers should refer these patients for eye examination.

Authors contributions

Olubanke Theodora Ilo (1st Author)

Olufemi Emmanuel Babalola (Co-Author)

Kuburat Oliyide (Co-Author)

Michael Olufemi Kehinde (Co-Author)

Folasade Akinsola (Co-Author)

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

None of the following Authors declare have any competing financial interests or conflicts of interest related to this submission: Olubanke Ilo, Olufemi Babalola , Kuburat Oliyide, Folasade Akinsola.

References

- Mehrnaz D, Azimi G (2003) Sickle cell disease: A behavioral approach to a systemic disease. J Behav Opt.14 (1): 3-5.

- Roy H (2020) Sickle cell disease.

- Donald A, Lee M, Jampol LM, Maurice FR. Sickle cell disease. In Duanes Clinical Ophthalmology on CD-ROM. Lippincott and Wilkins 3: 17.

- Akinsola FB, Kehinde MO (2004) Ocular findings in sickle cell disease patients in Lagos. Niger Post Grad Med J. 11(3): 203-206.

- Fadugbagbe AO, Gurgel RQ, Mendonca CQ, Cipolotti R, Dos Santos AM, et al. (2010) Ocular manifestations of sickle cell disease. Ann Trop Paed. 30 (1): 19-26.

- Lawton AW (1996) Sickle cell and the eye. ABNF J. 7(3):78-80.

[Pubmed]

- Osafo-Kwaako A, Kimani K, Ilako D, Akafo S, Ekem I, et al. (2101) Ocular manifestations of sickle cell disease at Korle-bu Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Eur J Ophthalmol. 21(4): 484-489.

- Ogundipe S, Obonna C (2010) Health Special: The burden of Sickle cell disorder.

- Serjeant GR(1974) Leg ulceration in sickle cell anemia. Arch Intern Med. 133: 690-694.

- Akinyanju O, Akinsete I (1979) Leg ulceration in sickle cell disease in Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 31: 87-91.

- Koshy M, Entsuah R, Koranda A, Kraus AP, Johnson R, et al. (1989) Leg ulcers in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 74: 1403-1408.

- Mack AK, Kato GJ (2006) Sickle cell disease and nitric oxide: A paradigm shift? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 38: 1237-1243.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS (2004) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 17: 410-416.

- World Medical Association (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama. 310 (20): 2191-2194.

- Goldberg MF (1971) Classification and pathogenesis of proliferative sickle retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 71(3): 649-665.

- Hsu J (2021) Sickle Cell Retinopathy.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS (2004) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 17: 410-416.

- de Oliveira Filho RA, Silva GJ, de Farias Domingos I, Hatzlhofer BLD, da Silva Araújo A, et al. (2013). Association between the genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase (GSTM1 and GSTT1) and the clinical manifestations in sickle cell anemia. Blood Cell Mol Dis 51(2): 76-79.

- Altman IA, Kleinfelder RE, Quigley JG, Ennis WJ, Minniti CP(2015) A treatment algorithm to identify therapeutic approaches for leg ulcers in patients with sickle cell disease. Int Wound J. 2015.

- Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S (2009) Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 324 (5931): 1190-1192.

- Minniti CP, Eckman J, Sebastiani P (2010) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 85:831-833.

- Emerson GG, Lutty GA (2005) Effects of sickle cell disease on the eye: Clinical features and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 19: 957-973.

- Walton W, Von Hagen S, Grigorian R, Zarbin (2002) Management of traumatic hyphema. Surv Ophthalmol. 47:2 97-334.

- Monfort JB, Senet P (2020) Leg Ulcers in Sickle-Cell Disease: Treatment Update. Adv Wound Care. 9(6): 348-356.

- Nwagu MU, Omokhua GI (2020) Treatment of recalcitrant chronic leg ulcer in a known sickle cell anaemia patient using honey and fresh hbaa red cell concentrate in a Nigerian secondary healthcare facility. Ann Afr Med. 19 (4): 278-281.

- Minniti CP, Eckman J, Sebastiani P (2010) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 85:831-833.

- Babalola OE, Wambebe CO (2005) Ocular morbidity from sickle cell disease in a Nigerian Cohort. Niger Postgrad Med J. 12 (4): 241-244. [Google Scholar]

[Pubmed]

- Balo KP, Segbena K, Mensah A, Djagnikpo P, Mihluedo H, (1995) Retinal complications in hemoglobinopathies. Med Trop. 55: 450-453.

Citation: Ilo OT, Babalola OE, Oliyide K, Kehinde K, Akinsola F (2022) Leg Ulcers: Associated with Sickle Eye Disease. J Clin Exp Pathol. 12: 414. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000414.

Copyright: © 2022 Ilo OT, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1473

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Dec 06, 2023]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1274

- PDF downloads: 199